It took half a century for James Halliday to accumulate his $1m collection of rare Burgundy wines. But at 82, he can’t drink them all. (Like many of us with cellars so full that they will never be drunk while we are alive).

James Halliday tells the story…

More than half a century ago I went to wine appreciation lessons conducted by the great Len Evans and I introduced myself to him, with no idea what it would lead to. From 1965, when he was appointed national promotions executive of the Australian Wine Board, until his death in 2006, he towered over the Australian fine wine landscape like no one before or since. My relationship with him started as mutual friendship, but deepened to one of unconditional love.

In the late 1960s, relatively early in our friendship, I went to Len’s house in Greenwich on Sydney’s north shore for dinner and gave him a fly-casting lesson – I have a lifelong passion for fly-fishing – on the large lawn behind his house. The lesson over, he thrust a glass of red wine towards me. “What do you think of this?” he said.

I remember the following moments as clearly as if they happened yesterday. As I moved the glass towards my nose, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up, and as I started to fully inhale the aromas I was literally rooted to the spot. I had never imagined that any red (or other) wine could have such an exquisite bouquet, one that offered yet more joy each time I swirled the glass. I lost myself in that bouquet, forgetting to taste the wine, and then, shaking myself out of the reverie, I thought: I’m afraid to taste it, lest it is less magical – a reaction I have experienced many times since.

Instead, I took a sip, and experienced a cathedral of tastes beyond description; mere words are inadequate to do it justice. In a strangled voice, I asked: “What is it?” The answer: a 1962 La Tâche from the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, maker of the world’s greatest wines, and some of the rarest.

I have now been collecting (and consuming) wine for more than 60 years, initially with a focus on Australian wine, then expanding to experience the great wines of the world. I have written more than 70 books, and have judged wine in Australia, Europe and the US, with years as chair of the National Wine Show of Australia and at capital city wine shows. I first made wine in the Hunter Valley in 1973, as a co-founder of Brokenwood.

Throughout all these years, the jewel in the crown of my cellar has been the wines of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. I bought my first bottle of wine from the Domaine (the French equivalent of “winery”) in 1969 or 1970, and over the years have amassed a collection, stored in the cellar under my house, that has fluctuated but currently stands at 260 bottles.

While I have shared many bottles over the decades with friends who venerate the Domaine, I have never sold any of its wines – and the Domaine does not encourage it. As I approach my 82nd birthday, however, I have decided to sell my entire collection, which auctioneer Langton’s has given an estimated worth of upwards of $1 million.

The Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, located inBurgundy, northwest France, comprises six main vineyards, each with its own appellation – the smallest somewhat confusingly named “La Romanée-Conti”. Four vineyards date back to the 7th century, when the construction of the Abbey of Saint-Vivant de Vergy began. In 1760, Prince de Conti bought La Romanée-Conti for an exorbitant price and promptly reserved the entire production for himself. After the French Revolution there were several owners until 1869, when the core of the present day DRC was assembled.

The La Romanée-Conti vineyard was zealously protected from the scourge of phylloxera that swept Europe in the last quarter of the 19th century, but nevertheless the pest gradually affected yields on this hallowed ground; the 1945 vintage amounted to only 600 bottles so the vines were ripped out, the next vintage coming in 1952.

It’s hard to imagine now, but it was not until 1959 that DRC’s grape-growing and winemaking business created a profit, and the first small dividend was paid to family shareholders. When shareholders through much of the 19th century sold their holdings it was not because they made a profit by selling, but because they could not sustain the losses. In earlier centuries the wealth of the nobility made the losses immaterial, and for 500 years various orders of the Church had no such thing as a balance sheet to consider.

The value or price of a Domaine de la Romanée-Conti wine cannot be calculated by a simple price/earnings ratio. On the secondary market a price of $20,000 for a bottle of la Romanée-Conti is the minimum, and an average production of 5500 bottles per year gives rise to gross sales of $110 million a year. But such calculations are irrelevant. The families are not going to sell, period. The French Government would not condone a sale to a non-French bidder at any price. And now it is a case of the Domaine seeking to restrain prices. Highly sought after by collectors in the US, Japan, the UK, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and recently China, all the Domaine’s releases are on allocation: the distributors in various countries take what they are offered. Bottles are numbered, and the Domaine has made it clear to its distributors that if a wine is sold shortly after delivery, those responsible won’t be allocated wines the next year. Quiet cash sales that don’t create a ripple continue, of course.

As collecting swelled my cellar – eventually to 10,000 bottles – I was constantly on the lookout for bottles from the Domaine. But even in the early years they were seldom, if ever, to be found on retailers’ shelves. I have bought DRCs at Christie’s auctions in London, from Negociants (the Australian distributors since 1984) and direct from the Domaine. The oldest bottles were from 1942, some notable vintages being 1948, 1962, 1971 and (my all-time favourite) 1978.

In 1998, my wife and I were among a group of wine friends, led by Gary Steel, founder/owner of Domaine Wine Shippers, who bought a house in the tiny town of Monthélie, France. Our visits have always been in May, and the most important of the numerous visits to the foremost Burgundy domaines was to Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. These days, the booming global interest in fine wine means it is virtually impossible to arrange a visit, especially if it is the first, and it’s now necessary for even longstanding clients to arrange a visit months before the event.

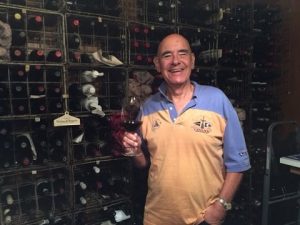

James Hallidays cellar. pix Julian Kingman

James Hallidays cellar. pix Julian Kingman

Over the decades I have staged or been to many great dinners featuring great Bordeaux, Burgundies and some of Australia’s rarest wines, dating from the 19th century. In 2005, a year before Len Evans’ death, a Single Bottle Club dinner had a magnum of 1929 Romanée-Conti as its highlight, purchased from a Belgian cellar for $60,000. Sixteen of the 27 wines were from 1929, and therein lies a song. Len was born in August 1930, a dreadful vintage across France; 1929, on the other hand, was a great vintage, and the year of his conception. So it was this we celebrated.

I have given freely of the greatest wines in my cellar for such occasions, because I absolutely believe these wines should be shared with those who understand and appreciate them. Domaine de la Romanée-Conti wines have usually been my contribution. Yet I have never sat down at home and opened a bottle of DRC to drink at dinner. Don’t get me wrong: if the occasion at home is a special one, I do not hesitate to open memorable bottles.

If anyone says, “But they’re so expensive/valuable”, my response is that it doesn’t cost me anything to bring them up out of the cellar. At one stage in the not-so-distant past I had more than half a dozen bottles of La Romanée-Conti – the most highly prized of all DRC wines – but haven’t been replenishing the stock because the market demand from all corners of the globe has taken the price to stratospheric levels.

Domaine de la Romanée-Conti gave me so much joy for so many years; it became central to my wine life. The joy has been enhanced by the pleasure, verging on a sense of awe, it has aroused in those who have shared the wines with me. I have the tasting notes and the menus from most of the 100 or so great dinners featuring DRC wines I have been to over the past 50-plus years.

My heart is deeply saddened by this sale, but I hope it will be the opportunity for the many wine lovers around the world to start or add to a collection of these wines. And my sadness has been assuaged by the knowledge that my memories of the wines will never fade.

Almost 60 years after it was made, that 1962 La Tâche is still a beautiful wine.

The Langton’s auction will be online and open from May 30 to June 28.

THE VINEYARDS

Echézeaux: A vineyard that produces highly expressive wines, with a seductive floral bouquet and a sweet red fruit palate, the tannins silky.

Grands-Echézeaux: Within the Domaine, this is simply known as The Grand, a clear endorsement of its quality. Its wines are richer and more structured than those of Echézeaux, with darker fruits and a hint of game (in the best sense).

Romanée-St-Vivant: I have always loved wines from this vineyard, even before the many improvements made in its management since the Domaine purchased it outright. It manages to be intense yet gloriously fragrant and fine as silk. I rank it third behind La Romanée-Conti and La Tâche.

Richebourg: Many devotees of the Domaine rate this vineyard second to La Romanée-Conti, pointing to the velvety power of its wines. I think Richebourg wines need longer to open up, and arguably emerge close to the best.

La Tâche: It has been said many times and proved many times that for the first 20 years or so, wines from La Tâche and La Romanée-Conti are difficult to tell apart. It is easy to rate La Tâche best because of the incredible fragrance of its wines and the prodigious length of their palate and aftertaste.

La Romanée-Conti: I’ve had more than my fair share of La Romanée-Conti wines over the years; the most compelling was a 1956, served blind in the Domaine’s cellars. The vines were barely 10 years old, yet it was a truly extraordinary wine from an appalling vintage.